Using Fandom in Activism: Story as Messaging

A guide to leveraging fiction for social reform. The second in a five part series.

Narrative is a crafted account of events. Narratives are art and entertainment, yes, but they are also news, history, culture, identity. Narratives are how we communicate, how we express ourselves and understand each other and our world, how we build identity and connect to others, both alike and different. Narratives move people, and through story-based strategy, narratives can move people to action.

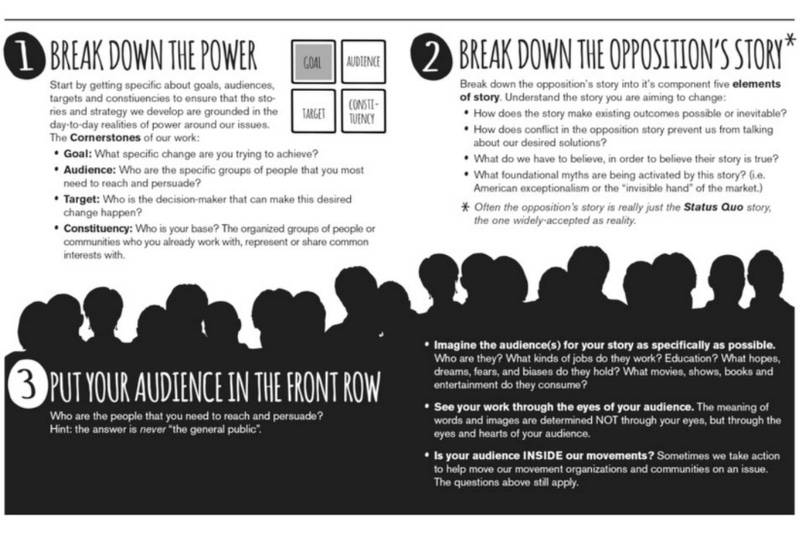

The Center for Story-Based Strategy provides guidance, tools, and resources for centering stories in social justice and liberation advocacy and activism. Below, I share examples of how existing fictional stories might be leveraged to communicate your message.

Charles Dickens

The collected works of Charles Dickens are a master class in the use of story as social justice messaging. As a journalist and novelist, he championed the poor and working class and condemned the institutions and individuals who exploited, oppressed, and otherwise disadvantaged them. His stories—including such well-known titles as Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, David Copperfield, A Tale of Two Cities, and the perennial A Christmas Carol—all critique the injustices of poverty and income inequality and detail how they bring spiritual and physical ruin to the people and systems that perpetuate them. Many of the characters and situations he created were based on real people and experiences, and they were written and published to be accessible to the common people as well as the more educated upper classes.

“[H]aving experienced the lower depths, he never ceased, till the day he died, to commit himself, both in his work and in his life, to trying to right the wrongs inflicted by society, above all, perhaps by giving the dispossessed a voice. From the moment he started to write, he spoke for the people, and the people loved him for it.” —My Hero, Charles Dickens, The Guardian

Dickens used his stories and speeches to make his points, but he was also politically active. He campaigned for fair wages and working conditions, advocated for prison reform, condemned slavery, and championed an overhaul of public education to benefit the lower classes. In his mid-thirties, he co-founded and ran a women’s shelter, Urania House, mainly for sex-workers, but generally for young women and girls who were homeless and destitute, and therefore likely to engage in crime. In his novel Oliver Twist, first serialized starting in 1837, the character of Nancy, a classic “hooker with a heart of gold,” embodies the type of woman he sought to house.

Dickens is a shining example of using story as social commentary and turning social commentary into direct action, so much so that the word “Dickensian” describes “living or working conditions that are below an acceptable standard.”

Explore More

Dickens and Urania Cottage, the Home for Fallen Women—Jane Rogers, The Victorian Web

‘He contains the whole of literature.’ Is Dickens better than Shakespeare?—Peter Conrad, The Guardian (2025)

Dickens and Contemporary Political Thought—Caleb Griffin (2023)

The Radicalism of Charles Dickens—Gareth Jenkins, Jacobin (2020)

Charles Dickens and the Politics of Fiction—Jan-Melissa Schramm, Cambridge University (2012)

“Charles Dickens”— John Kucich and Dianne F. Sadoff, The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature (2006)

The Political View of Dickens—Aloysius P. Dehnert, Loyola University (1947)

Marvel Comics

“If I were editing an underground newspaper or any newspaper and I had some sort of a message or some sort of a mission, it would seem to me I would want to present it in a way that would give me the widest possible audience.” - Stan Lee Talk Show Pilot 1968

My first foray into writing online professionally was with comic book blogs1, and it was through that I met A.J. and Karen. I wrote about comic books weekly for almost a decade, and at least once a month, someone somewhere would complain that the stories were “too political.” Or more to their point, “too politically correct”—in today’s parlance, “too woke”—not like back in their day when America was great and comics were fun stories about superheroes beating up bad guys.

Captain America a) was introduced during WWII, b) fighting for the Allies, c) by punching out Hitler, and d) his name is Captain America. Captain America always was and continues to be a political statement. What that statement is may be up for debate. One of the dangers of using stories as messaging is that different people experience, interpret, and recall stories differently. For example, The Punisher is an ultraviolet, vigilante antihero who works explicitly and exclusively outside the law, but his symbol has been appropriated by law enforcement, military, and various right-wing organizations dedicated to the concepts of ‘law and order.’ However, it is patently absurd to say that stories about Captain America, of all people, should be less political—and Disney’s backtracking won’t work.

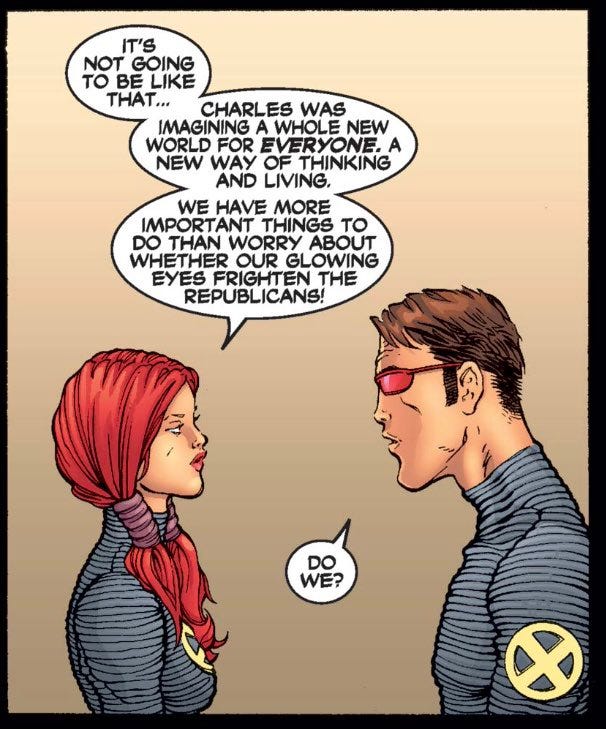

The X-Men are outcasts. Stan Lee, who originated the characters along with co-creator Jack Kirby, “thought it might be fun to get an analogy with the way some people are picked on by bigots.” I’m not sure I would call that ‘fun’, but the sentiment is sound, and has carried through the comics to the cartoons of my childhood and the movies that are still being made. In an interview with Buzzfeed in 2014, Sir Ian McKellen, a gay man who’s played my favorite mutant, Magneto, since the first X-Men film in 2000, told them “according to Marvel, young Jewish, Black, and gay people are the biggest readers of the X-Men comics” because “these are all people who, well, feel a little bit like mutants.” See also immigrants, transgender people, and everyone else who is marginalized and under attack for their identity.

Explore More

Jay & Miles X-Plain the X-Men podcast

The Judgment of Magneto—Asher Elbien, Defector (2024)

Yes, the X-Men Have Always Been Political—Josh Link, Substack (2022)

Captain America & Political Realism—Illegible Indian, Medium (2022)

How Stan Lee’s X-Men Were Inspired by Real-Life Civil Rights Heroes—Dante A. Ciampaglia, History (2018)

Stars and Gripes: Tea Party Protests Captain America Comic—Dave Itzkoff, The New York Times (2010)

A Bug’s Life

A Bug’s Life is union propaganda masquerading as the Great Illustrated Classics version of Seven Samurai. Pixar movies are bright and colorful and center toys, animals, superheroes, and children, but are imbued with adult sensibilities and focus on adult themes. This is obvious in films like Up (grief and aging), The Incredibles (midlife and nostalgia), Wall-E (loneliness and climate crisis), Finding Nemo (parenting and disability), and Coco (figurative and literal death), and it’s clearly part of their purpose. A Bug’s Life is generally considered one of the studio’s weakest, but it is an absolute banger in terms of social justice messaging. In the climax of the film, Flik explains collective action in terms a seven-year-old could understand.

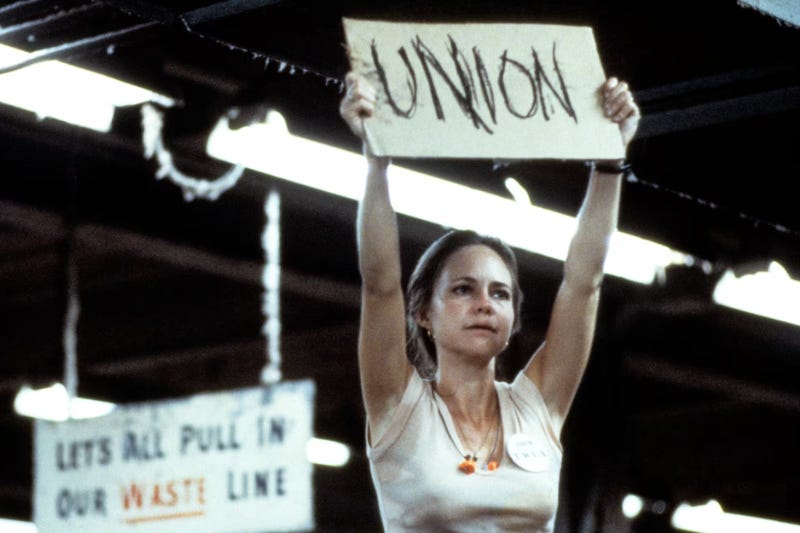

In 1983, 20.1% of workers were union members. In 2024, 9.9% of workers were union members. Reaching back to the Reagan presidency, conservative and corporate policy has been purposefully and openly anti-union. This is because they are scared. Collective action is communal. It prioritizes the many (all of us normie worker ants and weirdo circus bugs) over the 1% (the uber rich grasshopper class who depend on our labor to maintain their lifestyle of waste and destruction). Unions benefit everyone and remain popular. I am so pro-union that I belong to more than one. But collective action is not limited to bargaining or labor. Protests, voter registration drives, and boycotts are all coordinated actions with specific goals. Whatever your goal is, you can be like Flik and inspire all the other bugs to rally to your cause.

Explore More

What Unions Do—American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations

Majorities of adults see decline of union membership as bad for the U.S. and working people—Ted Van Green, Pew Research Center (2025)

Ronald Reagan Has Shaped U.S. Labor Law for Decades—Andrew Storm, OnLabor (2024)

A Bug’s Life at Pixar

Andor

Hope is a throughline throughout Star Wars2. The first film did not have a subtitle during its initial release. It became known as Episode IV after The Empire Strikes Back was billed as Episode V and in 1981 it was retitled A New Hope. In universe, the film takes place nearly twenty years after the establishment of the Galactic Empire, the Rebellion is depicted as small but organized, and the destruction of the Death Star is suggested to be their first big win. The first film, and the first trilogy, are a hero’s story and the hero is Luke Skywalker. He represents the Skywalker legacy, the reemergence of the Jedi, and the victory of the Rebellion. Leia reaches out to Obi-Wan as her only hope and he sends her Luke. Luke is a new hope. But Luke’s actions are the culmination of decades worth of work. Luke is not the only hero, he is not the only Jedi, he is not even the only Skywalker.

In Rogue One the phrase “rebellions are built on hope” (Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, screenplay by Chris Weitz and Tony Gilroy) travels from Cassian to Jyn to the Rebellion leadership. In Andor, we learn that Cassian first heard it from a bellhop on Ghorman during what came to be known as the Ghorman Massacre. The seemingly simple message is not merely aspirational but reflective. Instructive. Hope is not the goal. Hope is the foundation for action. Hope is what drives Bail Organa and Mon Mothma to plot against the Emperor. Hope is what keeps Obi-Wan and Yoda alive in their exile. Hope is what sends Leia from Alderaan to Tatooine, and Luke from Tatooine to Alderaan. Hope is what sends Rey to Ahch-to and Luke to Crait and Ben to Exogol. Hope is Padmé’s bequest to her children and hope is Leia’s legacy, her words used to remind the resistance to keep going: “Hope is like the sun. If you only believe in it when you can see it, you’ll never make it through the night.” (The Last Jedi, screenplay by Rian Johnson)

But hope is the beginning. Rebellions are built.

In Andor’s second season, the Imperials try to control the narrative by manipulating the events on Ghorman to cast the Rebels as dangerous and violent instigators who cause chaos and destruction (Hm). In “Welcome to the Rebellion,” which won an Emmy for outstanding writing in a drama series, Mon Mothma stands before the senate, and the galaxy of people watching, to reveal the false narrative, demand accountability, and encourage rebellion. Andor illustrates that empires are built on obedience, on authoritarianism, and they use subterfuge and despair to stay resistance. In contrast rebellions are built on not only hope, but collective action, mutual aid, coalitions, and infrastructure. In the galaxy far, far away, the Rebellion is made up of many different people and organizations who do not always agree on the details but are united in opposition to the Empire. Speeches and stories are calls to action. You can and should use your own words. But Andor’s are poweful.

“We will never have a better chance than this and I would rather die trying to take them down than giving them what they want.” —Kino Loy (1.10)

“I burn my life to make a sunrise that I know I’ll never see.” —Luthen Rael (1.10)

“Remember this. Try.” —Karis Nemek (1.12)

“The Empire is a disease that thrives in darkness. It is never more alive than when we sleep.” —Maarva Andor (1.12)

“The Empire cannot win. You’ll never feel right unless you’re doing what you can to stop them.” —Cassian Andor (2.1)

“We’re the thing that explodes when there’s too much friction in the air.” —Saw Gerrera (2.5)

“When truth leaves us, when we let it slip away, when it is ripped from our hands, we become vulnerable to the appetite of whatever monster screams the loudest.” —Mon Mothma (2.9)

Explore More

The Empire’s Shadow: the revolutionary politics of Andor—Jorge Cotte, The Nation (2025)

Andor Shows Us What Popular Culture Could Be—Jon Greenway, Current Affairs (2025)

Bail Organa Strikes Back—Anika Dane, Endless Anakin (2020)

This is the second post in my Using Fandom in Activism series. Follow along with me on Instagram and/or TikTok to see clips from the panel. My co-panelists are A.J. O’Connell and Karen Walsh.

I’m a Marvel girl at heart, but I promise to write about the politics of my beloved failson Bruce Wayne someday soon.

It does not escape me that Disney owns three of my four examples, and despite the last being in the public domain, also owns Dickens’ best adaptation. The current trend of media consolidation is bad for many reasons but I’ll reiterate my preference for quantity over quality because quality is subjective. We need more different people telling more different stories, always.