This review is part of my Mental Health in the Movies project and is a discussion of the film(s) portrayal of psychopathology and/or psychotherapy.

Content warning: the following includes discussion of suicide, self-harm, and disordered eating in addition to depression, anxiety, and psychosis.

Midway through Black Swan (Fox Searchlight, 2010) ballerina protagonist Nina Sayers explains the plot of Swan Lake to her date: “It’s about a girl who gets turned into a swan and she needs love to break the spell, but her prince falls for the wrong girl so she kills herself.” This is also a summary of the film: “It’s about Nina who has a psychotic break and she needs care to break the spell, but her community prioritizes the fantasy so she kills herself.”

At no point does Nina Sayers receive a diagnosis of mental illness or even speak with a healthcare professional. With nothing explicit, her illness has been interpreted as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, or body dysmorphic disorder. Some of her symptoms match each of these, but none are a perfect fit. Nina is a perfectionist experiencing psychosis. She hallucinates and becomes increasingly paranoid throughout the film. Her eating is disordered and she practices self-harm. She is anxious, moody, and temperamental. Nina is fixated on the romantic tragedy of Swan Lake and she ultimately kills herself in tribute to it.

However, while Nina is clearly and explicitly suffering from mental illness, many of her symptoms are considered standard for an elite ballerina at the height of her career. Ballet is an unforgiving art form. It requires rigorous training and exceptional discipline. This attracts perfectionists like Nina. But the requirement to host strength, power, and agility in a tiny, pretty body creates disordered eating. The highly regimented time and repetitive exercises can slip into a compulsion. Pain and injury are not only a constant, but a source of pride and proof of commitment, of desire, and of will. Ballerinas are beautiful and silent. Do these stringent conditions attract a certain type of mentally ill personality and do they cause, contribute to, and/or exacerbate mental illness?

In her memoir, Dancer Interrupted, Susan Priver describes her experiences with ballet and depression. Her first major depressive episode happened when she was a teenager; after years of hard work she was granted a full scholarship to study full time at the School of American Ballet in New York. They provided training, lodging, and school accommodations. She was elite, special, and invited to fancy private parties for investors right away. She had a clear path to her dream of joining the New York Ballet Company. But instead of feeling joy, pride, or satisfaction, she was depressed.

“At sixteen, my whole life was ahead of me. I was in a place that I could actually make it all work. But, something was happening to me internally that was incredibly new. Suddenly, I didn’t love moving anymore. I was experiencing my first depression. In this strange physical manifestation my mouth would get dry, making it hard to swallow, and surprisingly, to speak. I was strangely over-taken with anxiety and sadness, even though with my newly received Ford Foundation Scholarship I certainly had a lot to be grateful and happy about.”

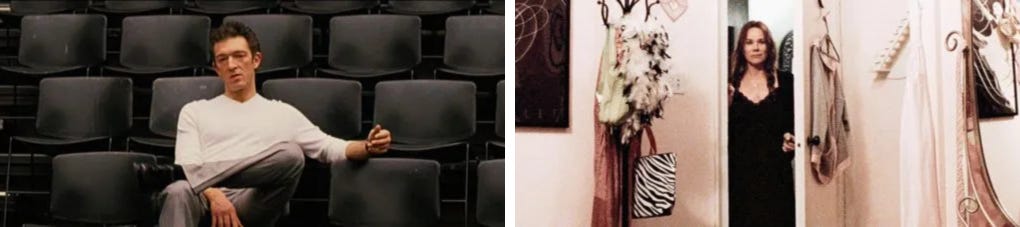

Nina, like Priver, starts to dissociate just as she’s realizing her dream. We watch her struggle with her emotions and her identity as the stress of being the Swan Queen turns her achievement into a waking nightmare. The movie recreates the horrors of psychotic hallucinations — her reflection moving, her skin growing scaly, unidentified noises in the dark — which allows the audience to experience Nina’s paranoia along with her. As she loses her grip on reality, Nina starts to make mistakes in rehearsal. This causes the director to assign an understudy which strengthens Nina’s fear that she is being replaced.

When Priver fell, only one of her classmates came to help her. “Not another person, including our teacher, noticed that I’d fallen. Class went on as though I wasn’t even there.” As Priver describes it, “They kept going [because] they had to. Only the strong survive.” The early casting scenes of Black Swan highlight this type of competitiveness and the resulting cruelty of the process. In ballet, members of the corps must dance as one entity, with each dancer’s individuality disappearing into the whole. Soloists are expected to stand out, but still essentially disappear into the role. In such an atmosphere Nina’s identity disturbance is easily understood.

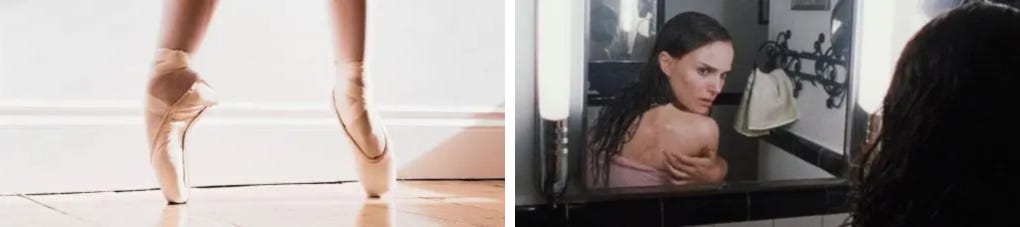

But injury is also the norm in ballet. Elite dancers regularly perform with bruised and even broken toes. In her book Don’t Think Dear: On Loving and Leaving Ballet, Alice Robb explains “Pain is the body’s warning system: nature’s request that we stop what we are doing. But from an early age, dancers are inducted into a perverse relationship with pain. It isn’t a sign that the body is under stress; it’s a source of pride, a sign of progress—something to be ignored, if not outright relished.” For Robb herself, “If I was supposed to feel pain, then I didn’t want to skimp on it. I wanted bunions, blisters, bleeding toenails, and I envied the girls who bruised more easily. If my feet looked whole, I felt like a fraud.” Is this a description of dedication or potential self-harm?

Throughout Black Swan Nina finds evidence of self-injury on her body and we witness her picking at hair follicles and minor lacerations. Due to the psychological horror genre of the film it’s not clear how many or much of these scenes are real or hallucinations. But Nina’s mother accuses her of “scratching” which indicates there is at least some truth to it. Non-suicidal self-injury can be a coping mechanism for people whose emotions are dysregulated— those who either feel too much or too little, or who slingshot between the two extremes. Their emotional pain is so uncomfortable that they use physical pain to manage it.

For some, the sensation of physical pain feels better than the absence of feeling that occurs in depression. While going through a depressive episode so intense Priver found it difficult to move, never mind dance, she told a psychiatrist “I don’t feel anything anymore…I feel blank.” Self-injury can also cause relief through pain offset: cutting causes physical pain, stopping the cutting causes physical relief which also affects the emotional pain. Robb describes dancing en pointe, indeed even standing en pointe, as always painful. “I don’t remember buying my first bra or trying my first drink, but I remember the thrill of easing my feet into pointe shoes for the first time; of learning how to crisscross the ribbons over my ankles and tuck in the knot so it didn’t show—it might cut into my ankle, but at least it wouldn’t disturb the smooth line of my leg. I remember how elegant it looked and how the pain, when I stood up, was shocking. I would perform this ritual countless times in the coming years, but I would never get used to it; the pain was fresh every time.” Relaxing, and releasing her feet from the binding shoes, was then a welcome sensation.

Self-injury is often correlated with eating disorders. Robb quotes Gelsey Kirkland describing her eating disorder as “an inevitable side effect of the ‘concentration camp aesthetic’ that dominated the New York City Ballet: it was, she argued, a reasonable response to the pressures of her environment.” Dancers are known to exist on the meagerest of calories and Nina shuns food throughout the film. Hunger, low blood sugar, and a lack of sleep can cause hallucinations and paranoia such as Nina experiences. And Priver notes that her extreme diet has a hand in her first depression during school. She relates that just before she left for New York “my obsession with staying bone thin was starting to affect me. My energy was waning from dancing on about eight hundred calories a day.” Within about six weeks she was injured. But the trade off to hunger, injury, and psychosis is the lightness of the dancing.

Both Priver and Robb describe dance as an elevated sense of being. Robb relates “Like hypnosis or dreams, [dance is] a conduit to an altered state and a sense of oneness with the world.” and suggests “Even as the trappings of ballet—the competition, the impossible physical standards, the punishing hours—can be a source of profound anxiety and distress, ballet itself—the movement, the music, the choreography—is simultaneously a salve for these emotions.” Priver describes her dancing as a defense against depression. “I needed to dance to make sense of the world and to feel like I had a purpose. I needed those endorphins that kept me from falling into the depths of life’s dark corners.” An introduction to yoga at a month long physical retreat is what finally helped reconnect her emotional self to her physical body and pulled her out of her depression.

Achieving perfection is Nina’s stated goal throughout the film. And dance is her chosen method. To Nina all the pain, the stress, the long hours, the hunger, and the isolation are worth it so long as she dances perfectly and therefore becomes perfect. Nina idolizes Beth, the newly retired prima ballerina of her Company whose position she is then elevated to. After her retirement Beth is injured. Thomas Leroy, the ballet director, tells Nina “She walked into the street and got hit by a car. And you know what? I’m almost sure she did it on purpose. … Because everything Beth does comes from within. From some dark impulse. I guess that’s what makes her so thrilling to watch. So dangerous. Even perfect at times, but also so damn destructive.” Leroy admires Beth for her artistry and her instability and enables, even encourages Nina to emulate both.

As Nina’s psychosis progresses she swings between anxiety and an eager, almost grandiose, self-assurance. Her hallucinations and delusions create paranoia and cause her to lose track of time but the intensity of her emotions also gives her confidence. Leroy directs her to “let go” and to be more like free spirited Lily, her rival dancer, and in the attempt Nina’s behavior becomes more reckless but more assertive. She stands up to Beth’s cruelty and to her mother’s emotional abuse. She lets loose dancing and socializing with Lily and two generic men they meet in a bar. She experiments with drinking and drugs. She seeks sexual pleasure with Lily, the generic men, and Leroy. But not all these moments of indulgence are real. Nina imagines herself as desirable and powerful but can’t tell when it’s true and when it’s a trick.

Nor does she get any help. As with Priver’s fall at the American Ballet School, only Lily seems to notice or care about Nina’s mental and emotional state. Leroy is most concerned with the ballet, with his own standing and legacy. He pushes Nina to lean into her fragility to aid her performance of Odette, the White Swan, and to set free her demons to aid her performance of Odile, the Black Swan. But when she starts to be unstable and unpredictable, he moves his attention to Lily, just as he moved on to Nina when Beth hurt herself. This is in keeping with both Priver’s and Robb’s depictions of the artistic directors they worked with and around. They are exacting, they cycle between showering praise and screeching abuse, and they create an atmosphere of intense pressure and few-to-no boundaries or sense of individual agency. Robb writes “I was so accustomed to hearing renowned dancers described as the muses of great choreographers that I had come to think of it as an aspirational title. I hadn’t considered how outdated the term is, how sexist and objectifying—how it implies that a woman’s role is not to create art but to passively inspire it.” Priver describes how “Dancers often don’t have a voice to say ‘no’. We’re told what to do and do it.” and how growing up under that pressure interfered in her ability to have healthy relationships long after she stopped dancing. She allowed men to use her body however they liked, and had a long term relationship with a much older, married Russian businessman who was verbally, physically, and emotionally abusive throughout their association. When she tries to break up he says “Perhaps you will finally get a self.” and when he finally leaves he tells her his abuse was necessary in order to make her a great actress and a complete person. Priver realizes it was the same message she got from her ballet mentors.

Nina’s mother, Erica, is a former ballerina herself. She was in the corps until she was 28, when she got pregnant. Erica believes she gave up achieving her dream of a soloist career for her daughter and is now hyper focused on Nina. Erica infantilizes and manipulates Nina to keep her dependent and to make sure she can neither surpass Erica in her career, nor grow confident enough to leave. Priver describes a complicated relationship with her mother, saying “I knew she loved me–especially when I couldn’t take care of myself.” and “She liked me being needy, the weak one, the underdog. It made her feel useful.” Robb writes more generally, “I remember the mothers who were always around, touching up their daughters’ makeup, hovering in the hallways during class, peeping through the door if they could. Monitoring and criticizing, offering unsolicited corrections.” and includes an anecdote about a twenty-nine year old dancer whose mother chaperoned their interviews and sometimes answered emails sent to the dancer’s personal address. She calls Erica in Black Swan “a caricature, but she has some basis in real life.”

In the final act of the film Nina debuts as the Swan Queen. Because of her mother’s manipulations she arrives late and has to threaten Leroy to keep him from sending Lily on instead. This impresses him and he tells her “The only person standing in your way is you. It’s time to let her go. Lose yourself.” Nina dances technically well in the first act, but stumbles at the end when she falls out of a lift and lands on the floor. Leroy screams at her that the ballet is a disaster and she flees to her dressing room. Lily enters, taunting, and Nina attacks her in a rage, stabbing her with a mirror shard until she bleeds out on the floor. Suddenly calm, Nina hides Lily’s body and the blood, finishes her make-up and takes to the stage as the Black Swan. She is electric. Powerful, seductive, triumphant, and the best she’s ever been. Leroy showers her with praise and she kisses him hungrily. She returns to her dressing room for the final act and Lily appears, alive and whole, to tell her how amazing she was as Odile. When Lily leaves Nina realizes she’d never been there in the earlier scene, that Nina stabbed herself. She swallows her pain and her fear and returns to the stage for the final act, the death of the White Swan. Again she dances better than ever before, is fully in every moment and every movement, and the audience adores her. Enacting Odette’s suicide Nina launches herself off a set piece and lands on a mattress. Blood pools out around her as Leroy, Lily, and the rest flock to her side shouting their approval only to find Nina bleeding out, a dying swan. “I felt it,” she whispers. “Perfect. I was perfect.”

Nina’s story mimics Swan Lake. The main cast are credited both as their role in the film and a corresponding character in the ballet. Nina hallucinates transforming into a swan and the score is written to include and reference Tchaikovsky. Swan Lake ends in a suicide so Black Swan must, too. The film won a PRISM Award for its accurate portrayal of mental health and is widely recognized as a compelling and creative depiction of psychosis. Based on Dancer Interrupted and Don’t Think Dear it is also an accurate portrayal of the ballet establishment and the mental and emotional struggles elite ballerinas face. If it is a stigmatizing representation of ‘madness’ it is also a stigmatizing representation of ballet. Perhaps most interesting is the blur between reality and fantasy that the film relies on to tell its story.

Alice Robb wrote her book because “The traits ballet takes to an extreme—the beauty, the thinness, the stoicism and silence and submission—are valued in girls and women everywhere. By excavating the psyche of a dancer, we can understand the contradictions and challenges of being a woman today.” Black Swan takes mental illness to an extreme, imbuing it with horror, sexualizing madness, and romanticizing suicide. Nina is the victim and the monster, fighting battles on every side. But at no point does the movie suggest anyone should want to be like Nina. She has everything she’s ever wanted and she’s miserable and afraid, literally losing her mind. Erica, Beth, and Leroy are all also wretched. The only one depicted as joyful and healthy is Lily. Lily is explicitly Nina’s opposite. Imperfect Lily is the aspirational character which suggests ballet does not require self-destruction but mental health does require maintenance.

Unlike Nina, Priver survives her depression and slowly picks up the pieces of her psyche and her life. She starts moving again. “Even though my life was slowly improving with the therapy sessions, the newfound outlet of yoga and hanging with my friends from the Hollywood YMCA, there was still a quiet desperation to prove to myself that I would be okay without my drug of choice: ballet.” Eventually she satisfies that desperation with a career teaching yoga and acting on stage. Robb became a writer. In five or ten years, when ballet has left Lily behind, she can become an artist. All of these ‘happy endings’ require therapy, time, nutrition, community, and self-reflection. Nina had none of them; that is her tragedy.

References

Dancer Interrupted, A Memoir by Susan Priver (2020)

Don’t Think, Dear: On Loving and Leaving Ballet by Alice Robb (2023)

Emotion Dysregulation and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Jennifer Wolff (2019)