This review is part of my Mental Health in the Movies project and is a discussion of the film(s) portrayal of psychopathology and/or psychotherapy.

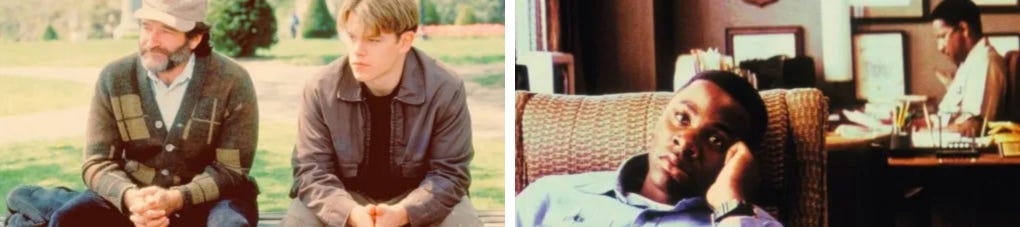

Good Will Hunting (Miramax, 1997) and Antwone Fisher (20th Century Fox, 2002) have a lot in common. Both films center young men, the titular Will and Antwone, who grew up in foster care and exhibit acute anger due to an abusive background. Both Will and Antwone are forced into therapy after getting into a fight, and both initially resist. Each film includes a montage of sessions in which the therapists wait out the patients when they refuse to speak at all. Both montages end with the young men giving in and starting to open up. And once they do, the relationships between patient and therapist shift rapidly. Over the course of only a few sessions, Will and Antwone become reliant on their therapists and come to see them as a father figure rather than a counselor, or even a mentor.

Hollywood loves an orphan. An orphaned character starts out damaged. It is the easiest road to both sympathy and empathy. Both Will and Antwone are introduced as violent and reticent, but we are told almost immediately that those traits trace back to their lack of a family, to their lonely and abusive childhoods. This provides context but also excuses the violence, and suggests that if they were to find a family, they would be healed. And the story follows through by providing replacement fathers through therapy and setting up the promise of a future family through the love interests.

The goals of therapy and parenthood are not entirely dissimilar. The patient or child learns life skills and the therapist or parent provides support during their charge’s journey to self actualization. Particularly for a teen or new adult orphan, a therapist may act as a substitute parent. However, Sean and particularly Jerome cross therapeutic boundaries to become substitute parents to Will and Antwone.

There are plenty of examples of questionably ethical behavior on the part of the therapist in both films. The efficacy and ethics of self-disclosure by therapists is an ongoing discussion. In “More Than A Mirror” Zoë D. Peterson pointed out, “eliminating all therapist self-disclosure is impossible and possibly, in some cases, detrimental to the client’s treatment.” Given Will’s and Antwone’s violently abusive backgrounds and demonstrated caginess, some therapist self-disclosure can be seen as an avenue to build trust. And indeed, the conversational give and take puts the young men at ease and allows them to open up. However, Peterson also noted that “therapists must always consider how their self-disclosure will affect particular clients.” And in that, it’s not clear if Sean and Jerome failed to consider how their self-disclosure could harm Will and Antwone or if they considered the risk of harm acceptable. Neither choice paints them as particularly good therapists.

Specifically, both Sean and Jerome are overly involved in Will’s and Antwone’s love lives. Good Will Hunting overtly parallels Will’s burgeoning relationship with Skylar to Sean’s idealized relationship with his dead wife. Sean’s Dead Wife is not even enough of a character to have a name, but she comes up in nearly every interaction. To Sean, and eventually to Will, Sean’s Dead Wife represents the key to a life well lived. He gave up his career for her, he gave up a once in a lifetime baseball game for her, and since her death he’s barely lived. Until Will shows up. Will provides Sean with a problem to solve, and working on it, working on Will, fixes Sean. And that’s the main problem with Sean’s oversharing about his Dead Wife: it’s about him. Peterson again: “it’s exploitative and unethical to self-disclose if the therapist is using self-disclosure to get [his] or [his] own needs met.

In contrast to Sean, Jerome does not bring up his relationship to his wife until very late in the action. However, it is clear that the relationship weighs heavily on him. Berta is more of a presence than Sean’s Dead Wife, but she represents the same lacking. Sean had a perfect life with his wife but she died; Jerome was going to have a perfect family with his wife but she can’t get pregnant. And while the film does not parallel Antwone’s relationship with Cheryl to Jerome and Berta, it makes a point to depict Cheryl as a picture perfect wifey in the scenes with Antwone’s family, and to make it explicit their relationship is sexual and potentially fertile. Jerome’s self-disclosure about Berta’s infertility happens in the final scene but it colors everything that came before. Jerome wasn’t just accepting the role of substitute father for Antwone, he was actively seeking a son. He did not consciously adopt Antwone into the role, but it is nevertheless where Antwone ended up.

Another concerning behavior depicted in both films is the patient approaching the therapist at home. Antwone shows up on Jerome’s front step with a big grin because his date went well. Jerome very briefly suggests this is inappropriate but drops it within minutes and ultimately invites Antwone into his home, and then back again for Thanksgiving with his whole family. All of this is way past the line of healthy boundaries between a patient and a therapist.

In the final scene of Good Will Hunting, Will leaves a note in the mailbox outside Sean’s apartment. This is barely an infraction given that Sean doesn’t even see Will so he certainly doesn’t invite him inside or back for the holidays. It is only notable because it’s not explained how Will knows where Sean lives. Either Sean told him, which he should not have, or Will found it out, which is problematic, potentially stalker, behavior, and that’s an uncomfortable end to the film.

The use of touch in therapy is also an ongoing topic of discussion. Sean uses both aggressive and affectionate physical touch with Will, and both uses have a positive effect in the film. In their first interaction, Will verbally pushes Sean to the brink and Sean reacts by pressing Will against a wall and choking him. This is combative and blatantly unprofessional and unacceptable behavior. But Will responds well. He is interested in Sean, impressed even. That this response is likely due to his abusive childhood is not interrogated by the film, but it can be inferred.

In a later session, Sean again backs Will against a wall and lays hands on him, but this time to pull him into an embrace. The hug happens after Sean tells Will “[the abuse] was not your fault” over and over until he breaks into tears. Here the use of touch is less controversial; it appears to be an appropriate show of support during an emotionally charged moment. But the two scenes bookend Will’s therapy sessions with Sean which underlines how often Sean pushes the boundaries of appropriate therapeutic behavior.

There are a few emotionally charged moments of aggression between Antwone and Jerome, but nothing on the level of Sean choking Will. Possibly due to the military context, Jerome and Antwone are generally more measured and less confrontational than Sean and Will are. The most notable exception is the bathroom scene following Antwone’s graduation. Here they are so heated Jerome shouts for another sailor, presumably someone who simply wants to use the bathroom, to get out.

This scene is a turning point for their relationship and the film. Jerome pushes for Antwone to reconcile with his family throughout their interactions, but it is only when he threatens to stop seeing Antwone entirely that Antwone agrees to do it. The scene is a painful portrayal of the breakdown of a therapeutic relationship. Jerome is clearly struggling with the realization that he can no longer function as Antwone’s therapist due to his own actions inviting him home and allowing the familial relationship to build, to include his wife. He is trying to do the right thing by cutting Antwone off, but that is also harmful. Moreover, his attitude shifts upon Antwone’s distress. Jerome listens to new revelations about the killing of Antwone’s closest friend, and he offers soothing words and touch, all of which muddles everything more. There are no good choices for Jerome in that bathroom because he crossed the line ages before they got there. Still, he convinces Antwone to look for his family, which ultimately, if somewhat magically, heals them all.

The films differ wildly in their ‘happy endings’. Will chooses to follow Sean’s example and give up everything for a girl. He abandons his home, his new job, his Math mentor who got him out of jail, and his longtime friends who just bought him a car, to drive across the country on the off chance that Skylar, at whom he shouted “I don’t love you” in their last scene together, still wants to be with him. The decision is portrayed as romantic and fulfilling. Will will live his best life by being neither a Math genius with money and prestige nor a working class schlub with friends who’d lie down in traffic for him but a secret third thing that is wholly ambiguous except that it includes getting the girl. And Sean spent the whole movie telling everyone that that’s all that matters. So despite how bleak the end may seem to a critical eye, in the context of the film, Will gets a happy ending.

Antwone’s ending involves finding his father’s family, which leads to finding his mother. In quick succession he confronts the birth mother who abandoned him, the foster mother who beat and berated him, and the woman who sexually abused him when he was a six year old child. And then he returns to his aunt’s home to find it bursting with relatives and food, his girlfriend tucked into the back room of matriarchs, accepted as their legacy. He returns to Jerome no longer a virgin, having fought off his demons and embraced his identity. Jerome reveals that Antwone changed his life and they walk off to have dinner together. It’s implied that they’ve moved past the therapist-patient relationship and can now share the as-close-as-family relationship they want. Antwone and Jerome get a happy ending.

Movies rely on endings. They are not required to be happy or to provide closure, and there can be some ambiguity. But there has to be a climax and there has to be an ending. Good Will Hunting and Antwone Fisher follow the same outline and achieve the same ending: an angry young man is forced into therapy with the only therapist stubborn enough to help him come to terms with his abusive past and embrace his future. And they share the same problem: the character of the therapist is simultaneously exactly who the angry young man needs in his life and measuredly terrible at their job.

Sean and Jerome embody the ‘Doctor Wonderful’ archetype described in “On-Screen Portrayals of Mental Illness”: “Doctor Wonderful, who is attractive, selfless, dedicated, always available (to the extent that he/she may transgress boundaries) and extraordinarily skillful (e.g., often effecting dramatic cures by honing in on a single traumatic event occurring in the patient’s past).” But neither is a wonderful therapist outside of the reality of their film. Jerome facilitates and causes trauma for Antwone as well as he addresses it and Sean pats himself on the back and calls it a day after Will cries once. Jerome drags his wife into Antwone’s therapy and Sean gossips about Will with Gerry. Neither Jerome nor Sean suggest continued therapy past the one (1) climactic “breakthrough”. Will abandons his entire support system without a single goodbye to anyone, which is definitely not the act of someone who no longer needs therapy. Antwone is doing much better given that his support system has grown exponentially, his therapist has decided to remain his pseudo-dad, and he didn’t break up with his girlfriend a month or so before deciding to make her the only person in his life. But his continuing relationship with his therapist/dad blurs lines and also includes his wife. Notably, Antwone Fisher is based on a true story and Jerome is based on a real person— but the part he plays in the film is expanded. As the real Antwone Fisher, who wrote the screenplay, explains, “He’s a real person but I had to have him do some things that a few other people had helped me do. He also serves the purpose that he served in real life, and he also does things that other people did for me – just like the girl. Since you can’t have that many characters, you combine people.” In other words, Jerome is too good to be true.

Stephen Mcfarlane called ‘Doctor Wonderful’ “dangerous”: “The rapid cathartic cure is largely an invention of Hollywood… Its repeated depiction, however, creates a sense of expectation in patients, not only of what might underlie their problems, but how these issues can be resolved. The portrayal of wonderful psychiatrists as always being available (‘You can phone me, day or night’), willing to bend the rules, and open to (if not encouraging of) social contact out of hours is also potentially harmful, setting up an expectation of these boundary violations as a necessary part of therapy.” Will meets with a number of more traditional therapists before seeing Sean. They are portrayed as incompetent, easily annoyed, and unwilling to work with a difficult patient. Antwone only meets with Jerome, but the navy imposes a limit of three sessions on his therapy. Instead of arguing that this is not enough time, Jerome agrees to continue seeing Antwone in secret. In both cases, established therapy is portrayed adversely to breaking the rules. It not only suggests that Sean’s and Jerome’s behavior is positive, it suggests that therapists who exist in the real systems of the real world are by default inferior.

These portrayals may tell a good story, but they do not portray good therapy.

References

More Than A Mirror: The ethics of therapist self disclosure (2002) by Zoë D. Peterson

Antwone Fisher: How Dangerous is Doctor Wonderful? (2004) by Stephen MacFarlane